1965

The children are swinging on the back-porch glider. For once, not bickering “he won’t stop looking at me” or whining “she’s being mean to my Johnny West.” Through the screen door, refrains of Itsy-Bitsy Spider drift in. Looking out the window while I’m whipping instant chocolate pudding into creamy peaks, I find my thoughts going back to when I was younger when my mother made me “real” pudding. I still remember the recipe and, of course, the top layer of the skin that formed because she never covered it with Saran Wrap while it cooled. I use the instant, though, because it’s a busy mother’s best friend. The children prefer the homemade pudding my mother makes them, serving it warm with cold milk, but, oh well; instant is quicker. I wish there was an instant Yorkshire pudding and roast beef. Earlier this week, Jim requested that for dinner. If I had time, he said. He really has no concept of what it takes to run a household with two children. Yorkshire pudding. Don’t know why he can’t just be happy with crockpot roast and potatoes. But his mother made Yorkshire Pudding and oven roast for them every Sunday. I say a silent prayer that she passed before I met Jim. I can’t even live up to her memory; I can’t imagine living up to her if she were still here.

Pulling myself back to present time, I scoop the pudding into bowls and deliver their afternoon snack. They sing their praises. “We love chocolate pudding. We love swinging, swinging. We love singing, singing. We love mommy, mommy.” I tell them I love them too and turn around, eyeballing the line-dried clothes with a sigh. Today has been one battle after another. I had to call the plumber because Julie decided to flush an apple core. Jimmy can’t leave Julie’s Barbies alone; he says his Johnny West needs a wife. Julie won’t stop criticizing Johnny West, though, because he doesn’t have a white horse, so of course, Barbie won’t marry Johnny. Jimmy’s been whining all morning about wanting a white horse for Johnny West, even though his birthday has just passed.

“Itsy bitsy spider goes up the waterspout. Down comes the rain …”.

I hear a giggle from my daughter and then my son screams, “Mommy!” I glance back at them and see a blob of chocolate that looks like a large leach on my son’s cheek. I gasp and then shriek, “Why, why would you do that? Go, Get. To your rooms.

They try to argue with me, but I just yell louder, “Get. Just get. I’ve had enough of you two. AND no more pudding for you, Julie. Ever.”

Julie burst into tears, wailing, “I know you love Jimmy more than me.” Jimmy just stomps into the house, wiping pudding off his cheek and licking it off his wrist.

I am more than frustrated, but keep my mouth sealed. I will not go there with her again. Always whining that I love Jimmy more. Damn kids. Those damn kids. I should have never been a mother. I didn’t sign up for this crap when I made that decision. I just wanted a sweet baby to cuddle. Not these whining, fighting, never happy little terrors. I follow them into the house, ignoring their reasoning why they should not be sent to their rooms. “Go. Just get. You’ll stay in there until your father gets home.” This, of course, brings on another round of wails and tears, but I march them to their rooms and tell them to just shut up for once.

Back in the kitchen, I look at the lunch and snack dishes. I look out at the laundry hanging on the line. I sigh and open the under-the-sink cabinet door, reaching around the cleaning supplies, and pull out the bottle of vodka, take a pull, and another, and a third. Thank God for liquor. I go to my room and get a blanket and pillow, come back out, turn on the TV loud, and lie down on the couch. The drone of General Hospital helps drown out the sniveling coming from the bedrooms. My eyes start getting heavy; the images on TV are blurry; I’m so tired.

In my dream I’m back in 1949, and I’m seven years old. My dad just home from fighting in the big war. I’m in my nightgown, cuddling with him after my apple and peanut butter snack. I lay my head on the right side of his chest where the bird with my name is forever inked, and I pat the bird on the left side where my mama’s name laid claim to her bird. He says they are the swallow birds that kept him safe on his big ship. I kiss the star on the inside of his left arm. He says this helped him, and all the sailors, safely find their way home. Then in my dream, Mama is singing the sentimental journey song, “I’ll be waiting up for heaven. Counting every mile of railroad track — that moves me back,” but I know she is really singing for Daddy, who is gone in heaven. Mama continues singing, “Jonah in the whale, Noah in the ark. What did they do just when everything looked so dark? Man, they said ‘We’d better accentuate the positive. Eliminate the negative. And latch on to the affirmative.’”

I wake with a start, confused. The person and time are wrong. Mama didn’t sing the positive song. Auntie did. My mind comes to the present with the TV blaring: Mr. Whipple the supermarket manager scolding me to not squeeze the Charmin. I hear no sounds from the children’s bedroom. I swing my legs off the couch, my feet connecting with the shag carpet, go to stand up, and then my face is in the carpet. I touch my rug burned cheekbone, shake my head, and push myself into a sitting position. Freddy “Boom Boom” Cannon singing the “Action” song on the TV brought me fully alert; this meant it was 4:30 or so. Damn, I napped for an hour and a half. Still, no sounds from the children’s bedroom. I pull myself up and shuffle down the hall, head pounding, heart racing, thoughts zipping. What if they’re gone? I couldn’t live with myself if something happened. What if they got kidnapped? Like Charles Lindbergh’s little Charles Jr. who was taken from his crib: the story my mom always scared me with when she wanted me to stick close to her in the store. What will I tell Jim? I should not have drunk that vodka. They just had made me so mad.

The kitchen phone rings, but I ignore it and open my daughter’s door. I feel a punch in my gut. She’s not in here. I rush to my son’s room; they’re not there either. The phone had stopped ringing but now started trilling again, drilling into my sore head and cheek, making my eyes hurt. With clenched teeth, I rush to the phone.

“Hel … hello?’

“Do you know where your kids are?” I just about drop the phone but realize it’s my mother’s voice. “I’ve been calling you on and off. For over an hour. The kids came up here, wanting pudding. Said you was sleeping.”

I hear the sounds of her favorite show, Match Game, so I know what’s coming next and mouth the words as she says them.

“I ain’t got no time for this right now.”

She goes on to tell me how tired she is from work and how she just needs to sit, relax, and watch her show. How she didn’t want to make the kids homemade pudding, but since she didn’t have any boxed pudding, and I spoiled those kids rotten, she had to so they would shut their mouths and let her watch her show.

“So? Why didn’t you answer? You drinkin’ again? I thought you going getting the cure would stop that.”

I thought back to the month I spent in rehab and shudder. “No! Of course, I’m not.” I take a peek at my cheek in the mirror by the back door, wondering how I’ll explain the slight rug burn to Jim. “I can’t believe those kids. I can’t, just can’t, believe they’d sneak out of here and go ask you for pudding when they were grounded to their rooms because-”

“I don’t want to hear it. I’m sending them home now. You better not be drinking again. You know he said he’d leave you if you did.”

I stand there with the sound of the empty phone line droning in my ear. I place the phone receiver in its base. I’ve got about three minutes until the kids get here. I open the under-the-sink cabinet door, reaching around the cleaning supplies, and pull out the bottle of vodka, take a pull, and another, and a third. Thank God for liquor. I won’t take a fourth, though, so I can keep my wits about me. I look at the clock. 5:00. Jim won’t be home for another hour. I take another pull of the bottle, hiding it under the sink again, and go back to lie down on the couch, telling the kids they can watch TV until their Daddy comes home.

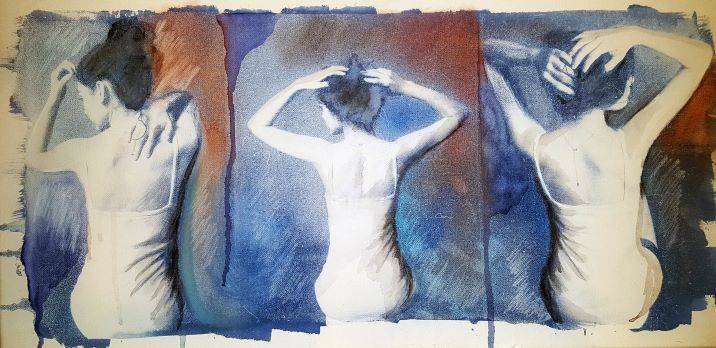

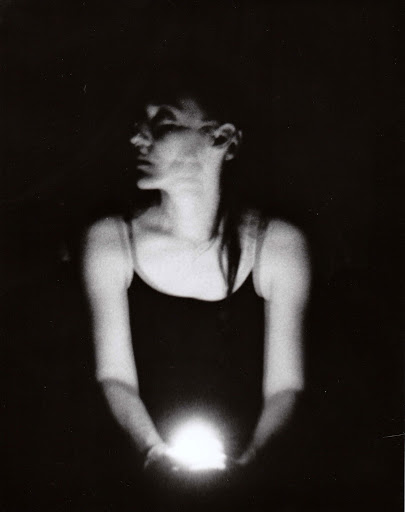

Tani Russell // Cyanotype prints, watercolor, on canvas

Author:

Since 2006, I have been a writing consultant at Morningside, but these pieces would not have been birthed without Steve Coyne and my peers in Creative Writing Fall 2019.

Artist:

Tani is a senior double major in Religious Studies and Studio Art. She explores photography, photographic alternative processes, encaustic, and various sculpture mediums.